- Home

- Judith Hooper

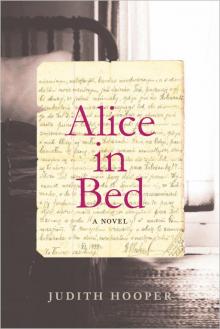

Alice in Bed Page 8

Alice in Bed Read online

Page 8

He had me lie down on his table. He loosened my clothing, and then his fingers were traveling lightly over me. He was like a dowser of the body, sensing unseen nerve currents beneath the skin. Eventually his hands would locate a spot of particular significance: a place below one armpit, an area at the top of my hips, a spot near my clavicle, a place high on the inner thigh. While his touch frequently embarrassed me and made me twitchy, his gentle manner reassured me. When he reached a spot of interest, he would cock his head to the side, as if hearing secret music inside me. If I tried to speak, he would shush me and explain that he was “reading” me now.

He had a habit of popping peppermint candies into his mouth and humming. There were always a series of notes that seemed to be leading to a tune but never quite arrived, which was frustrating to me. He halted his humming to ask me personal questions about my periods, their duration and intensity, and to predict that I should greatly benefit from bearing children—the sooner the better. On the third or fourth visit, he became engrossed in a spot four inches below my navel that was apparently associated with “hystero-epilepsy,” which I did not recall being told I had. What did it feel like to be hystero-epileptic? I could not bring myself to ask.

On the next several visits, his fingers inched into more intimate territory, not shying away from the triangle of my pubic hair, the junction of the inner thigh and the torso, the labia. Naturally, one had to expect this sort of thing from doctors, but this did not make it any less humiliating, especially as I sensed I was disappointing him continually with my tepid or flinching responses.

“Why are you so nervous, Miss James?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, here we will teach you to relax,”—using the royal ‘we’ as usual—“and your life will become more beautiful. You will see.” Patting my knee paternalistically. Yes, I thought, life would be better if I could relax, but how did one do it?

My body stiffened, erecting invisible barricades against his fingers, and Dr. M would gently massage away my resistance. His benign clinical detachment made it possible somehow to divorce his hands from the rest of him, and, for a brief period afterward, I felt as if I had honey running through my limbs. I did not know what to think about this.

On my seventh visit, Dr. Munro clucked his tongue and informed me that my uterus was “tipped” and this could explain the enfeebled state of my nerves.

“But how would this have happened?”

“Oh, it could be the result of an old horseback-riding injury or a fall or simply a hereditary defect.”

“I did tumble down a flight of stairs shortly after my thirteenth birthday.”

“We hear that sort of thing all the time, Miss James,” he said, brightening. “Don’t worry; we can remedy this in short order.” He strolled over to the wooden cabinets that took up most of one wall and drew something out of one of its drawers.

It was a shiny instrument of highly polished wood, with a handle and a rotating knob. He did something to it to make it purr, then rumble. He held it against my upper arm so that I could feel it vibrate. It seemed like an ingenious clockwork toy, and then alarm bells went off in my head. “What is it for?”

Dr. Munro smiled his gentle smile and said there was nothing to fear. Then he poked around with it a bit, finally laying the vibrating object against a part of my anatomy I’d always regarded as private. My body jumped as if electrocuted, and I barely suppressed a yelp, but I reminded myself that Dr. Munro was “the best in the business,” according to Aunt Kate. Did that mean that Aunt Kate had experienced this vibrating wand business? This was something I did not care to picture. When the instrument vibrated against another very personal spot, it was painful at first, and then turned to a sort of pleasure, which, in a way, was worse. I cried out involuntarily, as had occurred before only during my Emerald Hours with Sara. It was mortifying to experience this in Dr. Munro’s office, by mechanical means.

The doctor, however, congratulated me on having attained a “proper hysterical paroxysm.”

“Is that a good thing?”

“Yes, it is, my dear. The paroxysms are the body’s way of discharging hysterical energy. If you carry on with the wand, I predict you will be completely cured in no more than three months. You are fortunate, Miss James. Many ladies are unable to attain such a paroxysm.”

“Oh?” I was completely at sea now.

“Yes, and they can be identified by certain facial features, which are monuments, as it were, to a lifetime of dissatisfaction. Fortunately, these patients can in many cases be re-educated—not in their minds but in their bodies.”

“I see,” I said, though I didn’t.

Dr. Munro was willing—not to say eager—to prescribe a “wand” for home use if I felt so disposed. “Thank you. I don’t think that will be necessary,” I said politely. At the end of that day’s treatment, I dashed down his brownstone steps, nearly bumping into Mrs. Munro on her way up. She was a plump woman in a squishy layered bonnet resembling a meringue, and I wondered if she ever consoled herself with one of her husband’s vibrating wands.

A few days later I told my parents that Dr. Munro was not helping me, and they did not object to my discontinuing his ministrations.

At first I could not identify what the Dr. Munro episode reminded me of. Finally I recalled a strange conversation that took place years ago on the horse-omnibus that took the pupils from Beacon Hill to Mrs. Agassiz’s school in Cambridge. I was fifteen, a newcomer at the school, and was sitting beside Grace Coolidge, a new nonentity like myself. On the omnibus there was always a great deal of horseplay, shouting, tossing of hats and muffs, songs with multiple rollicking verses that everyone but Grace and I and a few others knew. I had no idea how to approach these clannish Boston girls.

The driver pulled over to the side of the road twice that morning to reprimand the pupils for not “behaving like young ladies.” From my seat, I could see the girls’ shoulders heaving in silent hilarity.

When we pulled over for the second reprimand, Grace turned to me and asked, “Alice, have you ever heard of the ‘local treatment’?”

“No. What is it?”

Well, she said, something dreadful happened to her aunt years ago and she swore on a stack of bibles that it was true. The aunt suffered from a form of hysteria known as “wandering womb” and went to a doctor for the “local treatment.” This consisted of painful manipulations and injections in the “female areas” and at some point—Grace’s voice dropped to a horrified whisper—the doctors placed leeches inside her and by mistake they crawled up into her womb.

“What do you mean, inside her?”

“You know, Alice!” She dropped her voice to a whisper behind her cupped hand. “Down there.”

The words “down there” immediately triggered a twinge down there in me. I crossed my legs; then finding that my thigh was pressing against “down there,” uncrossed them again.

“How ghastly! Did she die?”

“No, but she was never the same afterward.” The leeches weren’t meant to be in the uterus, she explained, but one or two crawled up inside. The pain was “beyond imagining,” she said. Her aunt, a spinster, became a lifelong invalid, queer in her mind and an epic hoarder of newspapers.

At the time I suspected that Grace made up this dramatic story to impress me, as mousy, unpopular girls are apt to do. (You have no idea of tall tales until you’ve heard the rumors that young girls circulate at school.) But after my sessions with Dr. Munro, I saw that such things could happen. It would start with casual questions, such as whether your periods were regular, whether you ever felt faint, and before you knew it, you’d end up with leeches in your womb.

I saw no more of Dr. Munro, but after my ordeal in his office, I did feel somewhat better, almost normal for a while. This was probably due to the sheer relief of being relieved of Dr. Munro’s massages and his tuneless humming. Aunt Kate attributed my improvement, of course, to the doctor’s skill.

WILLIAM

JAMES

DEAR ALICE

Your excellent long letter of Sept. 5th reached me in due time. If about that time you felt yourself strongly hugged by some invisible agency you may not know what it was. What would I not give if you could pay me a visit here! . . . I stump wearily up the 3 flights of stairs after my dinner to this lone room where there is no human company but a ghastly lithograph of Johannes Muller and a grinning skull to cheer me . . .

FIVE

1868

WILLIAM, MEANWHILE, WAS NOT IMPROVING AT ALL.

By the next steamer came a letter confessing that his health was actually very poor. His German servants were greasy and unclean, he wrote, and the thought of his breakfast plates being handled by them sickened him. And no window was ever opened in that land.

My servant here asked me in great excitement if I slept with the window open. She said there was a man in Weimar who slept with his window open and he became blind! Out in the street the slaw and fine rain is falling as if it would never stop—and the street is filled with water and that finely worked up to a paste of mud which is never seen on our continent.

Although permeated by melancholy, this letter was at least leavened by humor. As it happened, it was the last letter from Germany that would be read aloud to the family group. Subsequent ones were read silently by Father and tucked away like contraband. Harry and I knew from his expression not to ask.

When William arrived home in late autumn, I thought at first I was meeting his ghost. I wanted to shake him out of this trance or whatever it might be, because this was not the William I knew. Thin, hollow-eyed, and silent, he conversed without animation, shuffled his feet when he walked, complained of always being cold, even next to a roaring fire. When he held a teacup, the coffee splashed onto the saucer or the tablecloth, and it was heartbreaking to see how he tried to hide the tremor from the family.

“I don’t know what’s eating him,” Mother said. “He looks transparent, as if you could poke a hole right through him.”

Sorrow registered in her eyes before she snapped back to her default mode of taking care of business and pretending everything was fine. Being the only robust member of the James family was her cross to bear, as she shouldered the various illnesses, black moods, breakdowns, financial disasters, and heartbreaks of her children, whose temperaments were complicated and foreign to her.

“He keeps saying it is philosophical hypochondria,” Harry said. “I can’t make out what he means.”

If you asked William what was wrong, you’d get a long laundry list. His back had “collapsed,” his eyes were bad, his brain “moribund,” he could not concentrate or remember anything. And, on top of all that, he suffered from “severe dyspepsia and chronic gastritis of frightful virulence and obstinacy.” He took long walks in the cold and came back half frozen, pale and silent. He rarely joked now, and a humorless William was like an ocean without tides.

Mother had her theories. “He has too much morbid sympathy!” she complained to Harry and me. “The other day he was fretting about the servants having only one armchair in the kitchen. He wouldn’t stop talking about it!”

Dejected at seeing his wunderkind so fragile and unhappy, Father blamed Darwinism and other atheistic doctrines.

At meals William was either silent as a wax figure or twitchy and combative, starting painful arguments with Father. “I have read your article on Swedenborg, Father, and I can’t comprehend the gulf you maintain between Head and Heart. To me they are inextricably intermingled.”

“Then you understand nothing, William. You are as dense as the pusillanimous clergy.”

(The pusillanimous clergy were a favorite target of Father’s bombasts.)

“Your theory of Creation is a muddle, Father. I cannot fathom what you mean by ‘the descent of the Creator into Nature.’ You don’t explain it, and it seems to be the kernel of the whole system. You live in such mental isolation that I cannot help but feel that you must see even your own children as strangers to what you consider the better part of yourself.”

Father’s face clouded as he hacked at the roast with the carving knife.

When William remarked one evening that he was unable to decide what he should be, Father said, “Being is from God. A man cannot decide to be anything.”

William grumbled under his breath, “A nice life, provided you can live off your dividends.”

At Sunday dinner, hunched over his soup bowl, narrowly focused on keeping his spoon from shaking, William observed, “I am convinced, Father, that we are Nature through and through and that we are wholly conditioned, that not a wiggle of our own will happens save as a result of physical laws.”

I failed to understand why men took philosophy so personally, as if their lives depended on it. William, compulsively philosophizing, seemed to me like a person who persists in taking a drug that everyone else can see plainly is making him ill.

Father had lured William into science in the first place so that he could use its methods to corroborate Father’s theories of D.N. He even permitted him to go to Harvard, although he’d always insisted that colleges were “hothouses of corruption where it is impossible to learn anything.” William’s studies led him in the opposite direction, into a cold mechanistic universe, which was now tearing him apart.

In a household less metaphysical than ours such topics might have caused only minor perturbation. Here the father–son arguments raged loud and fierce, like the wars of the gods on Mt. Olympus. Father would say, “It is very evident to me, William, that all your troubles arise from the purely scientific cast of your thought and the temporary blight exerted upon your metaphysical wit. All scientists are stupefied by the giant superstition we call Nature.”

According to Father’s private religion, there was Nature and then there was Divine Nature. Only Divine Nature was real; “the world” was a sort of dream.

William would mutter, “Hmm, I wonder which of us is more stupefied by superstition.”

Father would say, “The first requisite of being a philosopher is not to think but to become a living man by the putting away of selfishness from one’s heart!”

“Not think? Really, Father?”

In an attempt to defuse the argument, Mother began to describe some gardens she had seen along Brattle Street, but no one took this up. Throwing his napkin on the table, Father shoved his chair back, scraping the floor, and limped into the other room.

“Oh, now you’ve upset your father!”

“It is equally true that he has upset me.” William got up and climbed the stairs wearily, as if he were a hundred years old.

“Henry has pinned all his hopes on William,” Mother remarked to Aunt Kate. “I don’t know why William can’t keep his ideas to himself. And now they are both missing dessert!”

“More for us then,” I said, attempting to insert some levity into the near-daily wrangle. Mother glowered in my direction.

“Oh, I think they both rather enjoy sparring,” Aunt Kate said.

William did speak excellent German; you could say that for him.

Then he astonished us all by reviving, like a plant that is given water. It seemed to occur overnight. He’d gone to bed wrapped in his usual listless melancholy and the next morning bounded down the stairs two at a time, and amused us by reading absurdities from the Boston Evening Transcript, such as a witness in a murder trial who testified that the corpse was “pleasant-like and foaming at the mouth.”

He went out in bright spirits, wearing a jaunty hat, a colorful waistcoat and gloves he’d picked up in Europe—he’d always dressed like a dandy—and took long, brisk walks for miles. If you accompanied him, it was like walking an eager, inquisitive dog that was always straining at the leash. He took up the Lifting Cure that had helped Harry so much and reported that his back was improving from day to day. He was suddenly full of praise for the “transparency” of American skies, without Europe’s veils and mists.

The dinner table arguments became less rancoro

us. Father would say, “I suppose, William, you still put forward the absurd argument that thought has a material basis?”

With a mischievous grin, William would reply, “A study of the mind apart from the body is utterly barren, Father.” Then Father would rail against scientists, and William would say, “Father, your ideas are untestable. It’s only a matter of time, you know, until we prove that the higher mental operations, like the lower, are functions of the supreme nerve-centers, obeying the same physiological laws of evolution.”

“Well, I pray you wake up to the enormity of your foolhardiness, William.”

But it was clear from their faces that their arguments were sport again.

Buoyed by the improvement in his health, William picked up medicine where he’d left off and applied himself to studying for his M.D. exam. Every so often he’d call me into his room to examine a slide under a microscope, showing me how to focus the lens on the teeming micro-world under the glass.

“Can you guess what that is?”

I squinted through the lens. “Nothing good, I expect.”

“That, young lady, is a polypus of the nose. Now—this one.” He put in another slide.

“A hundred gnats entombed in a custard?”

“An inspired guess, Alice, but this is Nutmeg Liver. The patient died of phthisis. If I ever have a patient with this condition I will know what it looks like microscopically.”

“Is there a cure for Nutmeg Liver?”

“Death is the only one I know of.”

“Then what is the point, William?”

“Oh, Alice, I don’t intend to practice medicine, you know.”

Alice in Bed

Alice in Bed